In an era of increasing flood risk, how can rural livelihoods be protected?

As widespread flooding becomes a more serious challenge for rural households and farms, we campaign for more responsive flood management and provide links to practical support

Weeks of relentless rain across the UK, particularly in the south west of England, have caused widespread flooding and waterlogging, leaving crops damaged, operations severely disrupted and an uncertain future for CLA members in the months ahead. In this blog we report on the situation for some rural businesses, provide links to further support for those affected and outline how we are working to shape Defra’s flood policies on your behalf.

Support for flooding

The following resources may be helpful if you have experienced flooding, or someone you know has:

- Forage Aid – a UK-wide charity, now part of the Addington Fund, that provides emergency forage and bedding for farmers hit by flooding and extreme weather, donated by other farmers. The Addington Fund provides one-off grants off up to £3,000 for the most vulnerable applicants

- RABI (Royal Agricultural Benevolent Institution) – provides free, 24-hour support for farmworkers, including mental health, practical, and financial support. The helpline number is 0800 188 4444

- Farming Community Network helpline – open from 7am to 11pm, it is confidential and free helpline (03000 111 999), which provides a listening ear and can guide you with further support

- RPA advice on what to do if flooding prevents you from meeting scheme obligations, including TB testing

- Environment Agency guidance on what to do if your slurry store is overcapacity or leaking due to extreme weather

- Citizens Advice and Shelter both provide guidance on what to do if your home has been flooded

- Government advice on how to safely clean your home after flooding

The UK Government can open financial support for flooded businesses and farms through the Flood Recovery Framework. This generally takes the form of the grants for individuals and business recovery, and discounts on council tax and business rates. For farmers, Defra sometimes offers a Farming Recovery Fund. Importantly, ministers determine the level of support and the eligibility criteria for these schemes each time a flood happens, so we don’t know if, when, or what will open following this year’s floods. You are therefore advised to check your local authority’s website in the weeks ahead.

Flood-hit areas in 2026

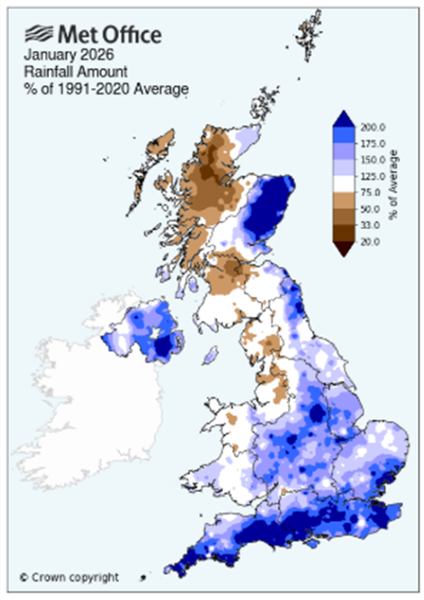

The start of 2026 has been exceptionally wet, although unevenly so as seen in the map below, with the worst rainfall in southern England. Cornwall experienced its wettest January on record. Many areas of the south west have experienced rain every day so far this year, with more to come.

Somerset in particular has been subject to widespread flooding, and a major incident alert remains in place across the county. Many are already drawing comparisons to the 2012 Somerset floods, which submerged more than 14,000 hectares of agricultural land and caused more than £10m in estimated damages.

Climate change is often linked to extreme rainfall like this. While it is likely to have played some role, it is tricky to know what its exact contribution has been. Climate change can therefore be a convenient thing to blame as it ignores the importance of river channel maintenance and wider land management in shaping flooding’s severity, which are strongly influenced by government policy and funding.

The long-term lack of river maintenance

In England, watercourses are split into ‘main rivers’ and ‘ordinary watercourses’. Main rivers are those more likely to cause damage if they flood and their maintenance is controlled by the Environment Agency (EA). Ordinary watercourses have oversight from the Internal Drainage Board (IDB) or council (in the form of the Lead Local Flood Authority).

Coordinated maintenance work – like routine vegetation management and removing sediment to maintain river conveyance capacity – sits with the EA not the IDB on main rivers, and riparian owners and other parties must obtain permission from the EA to undertake works. However, the EA only has a ‘permissive’ role in maintenance. It does not have an obligation to maintain rivers so it can largely pick and choose what it does.

Across the country, the EA has reduced the amount of maintenance it undertakes on main rivers. This is due to various factors, including:

- Central government reducing spend on maintenance relative to building new defences over the last decade

- Inflationary pressures on labour and machinery

- The EA’s use of national contractors which are more expensive than local IDBs, for example, because of the need to satisfy competitive procurement processes

- The EA’s lack of on-the-ground presence means it does not always catch maintenance jobs early, so they become bigger and more expensive

The real sting in the tail for land managers, however, is that the EA can decide to entirely withdraw its own maintenance responsibilities without downgrading the river’s classification to ‘ordinary watercourse’ - a change which would allow others to step in. This is what happened in Somerset last year, and reflects a pattern seen across England over several decades.

In August 2025, landowners across Somerset were informed that the EA had decided to withdraw maintenance on several main rivers, without prior consultation. The EA has now begun a process of consultation after local IDBs and other rural groups raised serious concerns about the risks from the policy. Whilst this is a welcome step, the fundamental problem of insufficient government funding for maintenance remains unchanged.

Lobbying for flood maintenance and solutions

More money for maintenance

The government needs to spend more on maintenance as a proportion of the total floods budget. This is good business sense as maintenance delivers £11 in benefits for every £1 spent, and is 2.3 times as cost effective as building new defences at preventing homes from flooding. The CLA emphasised this to HM Treasury in the Spending Review last June and in the government’s redesign of its floods funding policy. The government has now increased the total floods budget by 5%, has changed the allocation policy to make it easier to fund a category of maintenance known as capital refurbishment and has made it somewhat easier for the EA to move money between capital and maintenance budgets.

These are partial steps forward, but we will continue to argue for more focus on maintenance. For instance, at the most recent Floods Resilience Taskforce, which Minister Hardy chairs, we pushed strongly for this alongside the Association of Drainage Authorities (ADA) and the NFU.

Allow local groups to maintain rivers

The government needs to facilitate local groups and riparian owners who want to undertake more maintenance work themselves. This will involve declassifying more main rivers – a process known as demaining – so that riparian owners do not need to seek Flood Risk Activity Permits from the EA before beginning more extensive maintenance. It is worth noting that demaining is not a replacement for government-funded maintenance. It doesn’t necessarily come with budget for IDB-led maintenance, and IDBs can face challenging insurance costs – but on lots of low-risk rivers across the country demaining would make a big difference.

To help those on main rivers, the EA should introduce more classes of exempt activity to Flood Risk Activity Permits, and give IDBs trusted operator status so that they do not need to apply for fresh permits each time they work within eight metres of a main river. Currently, new types of exemption require parliamentary approval. The CLA would like to see the EA have control over deciding exempt activities, which we emphasised in a recent consultation on the topic.

Another route to local maintenance is to allow new IDBs to form, and existing IDBs to expand their boundaries. This requires change to the Land Drainage Act, which limits IDB scope to their 1991 extent. The previous government drafted legislation to open the door to these changes, which the CLA enthusiastically supported, but the current government has not carried the legislation through.

Instead of demaining, the government can also hand responsibility and budget to the IDB or LLFA for the main river through a mechanism known as a Public Sector Cooperation Agreement (PSCA). We have pressed government to use PSCAs more readily, but there has been little progress.

Upstream solutions

Improving soil health across catchment is essential to reduce the frequency of flooding because soils store millions of litres of water per hectare. If they cannot absorb as much rainfall due to compaction or crusting, then rapid surface runoff occurs, with water reaching rivers all at once across the catchment. Poor soil management causes soil erosion, which chokes rivers with sediment and reduces their conveyance capacity. We are working to challenge attitudes in policy to dredging – highlighting that many of our lowland rivers are heavily modified and do not have the discharge rates to flush sediment out – but it remains true that much of this sediment shouldn’t be in rivers in the first place.

The UK Government has a role here to design support for more regenerative ways of managing soil health, as a public good. The CLA is advocating for a Sustainable Farming Incentive that all farms can access, to provide transitional support to better soil management. But, there is also a role for industry to improve soil health as far as possible within current farm economics.

After a long period of piloting, the government is ready to mainstream natural flood management (NFM) techniques, and fund them from the main floods budget. The new floods funding policy commits £300m to NFM over the next ten years. Defra will also aim to align NFM with Environmental Land Management (ELM) schemes that fund NFM maintenance, something we highlighted was at risk of forgetting in the consultation on the funding policy.

Finally, after sustained advocacy from a broad church of organisations including the CLA, the government looks set to make Sustainable Drainage Schemes mandatory for new developments across England – building on Wales’s leadership and that of many local authorities. This should reduce the amount of runoff that enters rivers.

Final thoughts

Catchments across the country can become far more resilient to flooding, even as climate change makes our weather increasingly unpredictable. Achieving this will require landowners, government, the Environment Agency, Internal Drainage Boards and other parties to work together better.

We are not short of practical solutions, what is now needed is for the government to recognise the vital importance of regular river and watercourse maintenance, provide adequate funding and empower local groups to take action where appropriate to do so.